[ID:769] Delhi: In Hope of EquityIndia Meena and Sandeep, spend the day with their father just outside the metro station, on Saturdays when they have a half day at school. The siblings have invented their own games to occupy themselves while their father sells freshly squeezed orange juice. Sometimes, they play steeplechase to the electricity pole down the street, their finish line. The events of the race include jump over the concrete block, circle the tree, skip over the disused drain, hop onto the pavement and the final run to the pole, all this while carrying a bag of orange peels that has to be discarded at the garbage dump by the finish line.

The street on which Meena and Sandeep play sits in the city of Delhi. What their childish innocence perceives as an adventure of a steeplechase game is to others an experience of a physically challenging environment, an experience of disability. This experience is a part of all our lives, including the physically fortunate, the children and the elderly. As a woman walking on a lonely unlit street I feel ‘disabled’ in the face of the environment.

Delhi is the capital city of India and one of the nine districts of Delhi Union Territory. It is sprinkled with the physical and cultural remnants of at least 11 capital cities that date back to the early twelfth century. It has been called a city of many cities.

There is hardly an original ‘Delhiite’, most of its current citizenry immigrated here from states across the country. If you consider Delhi your home then you are a Delhiite. You are welcome to live here and share its offerings- the limited and precious space, the colorful street, the plenty trees that shade and occupy pedestrian pavements, the packed public buses, the shining metro train, the ubiquitous auto-rickshaws, the festivals, its tombs and ruins, its built heritage. This is the beauty and irony of this city.

Its demographic patchwork is reflected in its physical urban fabric. Physically we see Delhi as a collective of many fragments and parcels of development anchored in space and time by its precious ‘monuments’. These historic structures are a part of ours, the peoples’ collective memory and constitute a shared heritage. The city entices by way of contrast- the casually standing octagonal tomb raised on a plinth juxtaposed with contemporary construction is the story of Delhi’s built fabric.

In spite of being largely a planned city, the development of the city and the functioning of its systems has relied heavily on self-organization and informal, intuitive and often ingenious solutions that are born outside the system. But sometimes our ability to adapt, our resilience, gets the better of us it makes us accustomed to the policy and implementation failures of the administration and eye-washes of the government, and conditions us to accept uncomfortable and undesirable situations and circumstances far more than others. This particularly impacts the quality of life of the physically challenged, for whom such choices determine the difference between dependence and independence, between holding self-esteem and self-deprecation.

Being still a largely conservative society, it is pertinent to consider the traditional perspective of disability- the text Manusmriti lays down that a disable person reaps in this life the seeds of misdeeds that he had sown in his previous. It is a vicious circle that the common association with disability is of beggars using their physical impairments to solicit money at street corners and traffic signals. Even today, particularly in poorer and less educated families, the disabled members are shunned, pitied and at worst abandoned leading them to poverty and beggary. An attitude reversal is in urgent need.

Statistics ground us to the truth- according to 2001 census, 1.7% of the population- 2,35,886 citizens of Delhi is physically challenged, of which 49 per cent, almost half have a disability ‘of seeing’ (source: http://delhi.gov.in). In fact, a figure closer to 15 per cent of the population is believed to be more realistic for India by the United Nations.

In this scenario the city which fails to celebrate the diversity of its citizenry, its architects also become culprits. The government policy has played its role- in 1960 the education of children with special needs was moved from the ministry of education to Ministry of Welfare. In fact there is no political representation in any form of the physically challenged as of now. Two Departments: "Department of Social Justice and Empowerment" and "Department of Disability Affairs" were created under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment as recently as May 14th, 2012.

The Master plan of Delhi 2021, released only a year ago, makes many bold promises and begets much excitement for the future, but universal accessibility secured no more than a mere mention. The bye laws of the city, that were last revised 22 years ago, deserve the centre of criticism for almost entirely overlooking accessibility.

As a city we must accept that we have been callous and uncaring to the needs of the less fortunate. In a new born developing country, there seemed to be too many more pressing issues to be addressed, but now there is no justification for the uncoordinated fragmented efforts to generate accessibility that is universal. Monstrous ramps that occupy most of an unevenly paved pavement, is the image that comes to mind. It is time for a formal intervention to undo these half-hearted efforts that can only hurt the dignity of the disabled who receive as special treatment what others take for granted.

On the other hand, universal design as a concept of design is not unfamiliar to Indian Culture. Gaurav Raheja, an architect associated with universal accessibility cites the dhoti and the saree, that are traditional drapery garments unique to India, as exemplifications of the good sense of a ‘One size fit all’ approach. In the recent years, the relatively sensitive design of the metro rail and its stations is a heartening step in this direction.

The built stations provide inclusive features such as ramps with hand rails; guiding paths and warning strips for vision impaired persons; appropriate signage and audio announcements; elevators with lowered and tactile control panel; resting areas. Seats have been designated for wheelchair users, elderly and pregnant women within the coaches.

Samarthyam, a non-profit, has partnered with Delhi tourism and taken the lead in reforming the urban landscape. Their first project at Dilli Haat, popular craft ‘bazaar’ spread over six over, was widely appreciated. They created unobtrusive universal accessibility, meticulously detailed down to grab bars by urinals and beveled edge of the pathways. Since then, they have audited many prominent heritage structures, not only in the city but across the country- they have installed information plates in Braille at the Safdarjung Tomb in Delhi and designed barrier free paths to access part of the site. The site access stands similar for many other prominent sites of the city. Many bureaucratic buildings, meant to lead by example, have also been audited and ‘retrofitted’ for the sake of universal access.

Samarthyam has also played a crucial role in the research and design of the low floor buses by supplying the user groups’ perspective, back in 2005. Today Delhi Transport Corporation owns a proud and an ever-expanding fleet of over three thousand low-floor buses, equipped with an entry ramp that may be unfolded on request. However given the large volume of passengers particularly during peak hours, in practice the buses are seldom used by wheelchair users.

Heritage structures, because they are held so dearly close to our hearts, of all public structures are potentially amongst the most important benchmarks and teachers of accessibility. In Delhi, for the lay person, the historic structure and its premises represent open spaces- breathing space, public space, space to unwind or picnic on the weekend. Moreover, for us, a visit to a ‘heritage’ site is like re- uniting with family after many days away. Whether it is the visual delight of the balanced proportions of its form or the tactile quality of worn out smooth stones, most of these monuments are of the highest architectural character. A visit every so often is essential also because it reminds us of our roots. It is a space of reflection and conversation with the self as well as others around us bound together by this incredible legacy. Accessibility, both within and to the premises is the pretext to this precious experience that every person, every citizen deserves a right to.

Accessibility in design and architecture has focused on equitable use. We propose to take this concept to its next level and evolve it into its hyper or greater form that becomes a medium of unification that enables both, the able bodied and the differently-able to experience a new fresh, unseen perspective. It is about bridging the gap, beginning with the simple idea of making a monument accessible to everyone.

We propose a network of universally accessible monument sites which behave as nodes of an essentially accessible loop. If this network of universally accessible monuments and lines of transit is reinforced we can therefore regenerate the city and its sense of inclusion. To realize this vision, we borrow the concept from a familiar setting- the street. The street is alive with its many glorious textures, it is the business zone for the vendors and kiosks, a pitch for street cricket, a playground for children, a shelter for the homeless, a shortcut route for bikers, an arena for the amateur performers and a home to dogs and cows. This extraordinary spectrum of sensory stimulation heightens during festivals, each of which is accompanied by music, performance and ceremony, ranging from heat of the sacred bonfire on Lohri to the wet colours on Holi to the sounds and sparkles of fireworks on Diwali.

This is the exact quality that every aspect of our architectural heritage should attempt to reach out for. This concept addresses not only those who may have a specific sensory limitation but embraces the many who are perceptibly ‘normal’ by revealing the heritage in new, unprecedented and diverse ways to the senses.

On the ground, this multi-sensory experience is provided through subtle ‘invisible’ strategies, such as small scale and detailed tactile models of the structure, plantation of flower trees, visually contained access provisions that offer unique vantage points, sound and light shows, interactive educative installations particularly for children, echoing sounds that lend an idea of volume, light responsive sculptures, through theatre and musical concerts in the premises. It is also pertinent to exploit the capabilities of ICT ( Information and Communication Technology). The driving idea is that these strategy blend into the ambience, without overstating the chief/essential goal of accessibility. Each access strategy should be a result of a collaboration of stakeholders and user groups, verified by an access audit and a conservation assessment. These strategies may demand physical modifications - as custodians of this heritage, we must not be afraid to ‘intervene’ and adapt the structure to our renewed principles. Built Heritage is most relevant and best conserved, when it can make a positive contribution to our lives, not when it is glass-boxed and insulated.

Architectural heritage then becomes the stage for other spontaneous cultural expressions in food, music, and literature to be accessed, experienced, enjoyed, conserved and nurtured wholly.

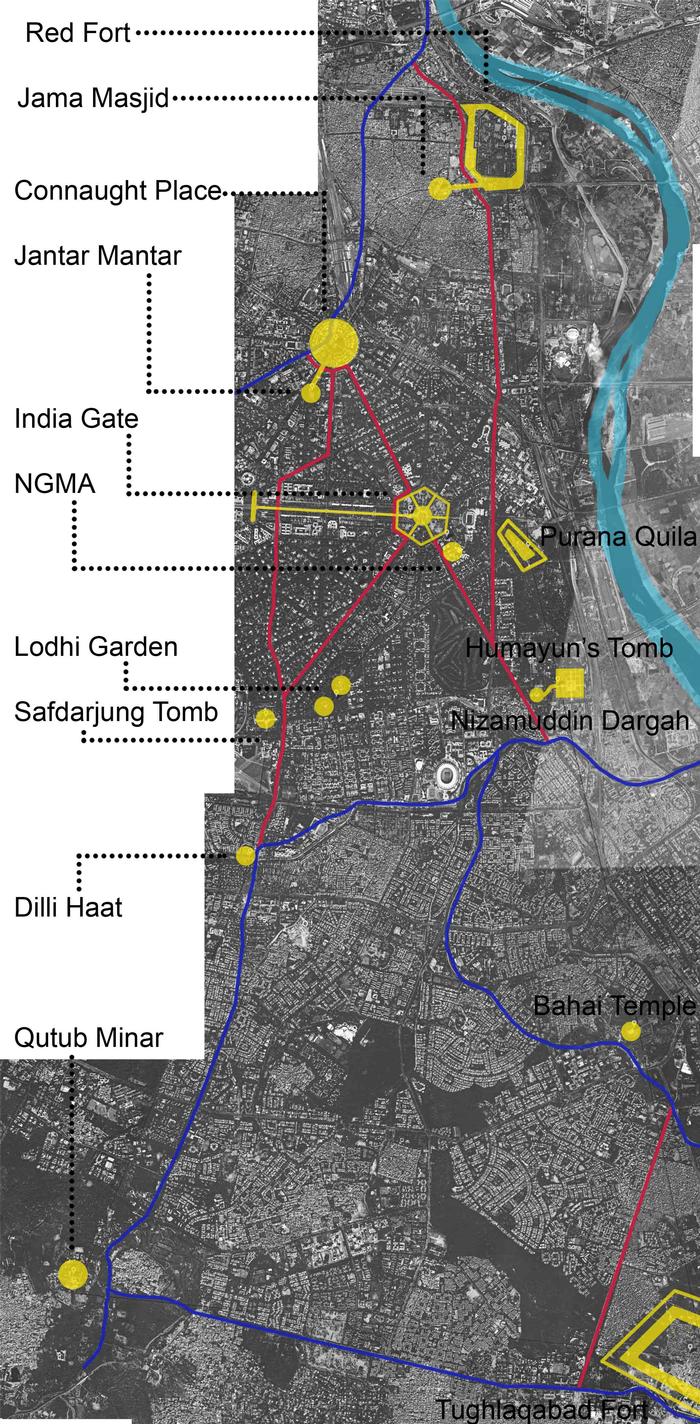

We further the start made by Samarthyam and the government by proposing a network of heritage structures that loops through Dilli Haat and Safdarjung tomb. The attached illustration shows one of many such possibilities- the nodal monuments include Qutub Minar, Tughlaqabad Fort, Bahai Temple, Humayun Tomb, Old Fort, India Gate, the National Gallery of Modern Art, Lodhi Garden, and maybe extended to encompass Connaught Place, Jatar Mantar, Red Fort and Jama Masjid. The idea is to span as many distinct eras, dynasties, architectural typologies and ambience as possible.

The lines of transit are mass public transport, that relies on inter-modality. We tend to blame the inefficiency of our systems on the large population, but in fact it is this very large group of users that ensures that every effort becomes viable! We propose to give the streets to the people and sink the vehicular roads. Exchange the pedestrian subways for a vehicle underpass and return the streets to the citizens. This non motorized zone will reinforce and complete the sensory stimulation of the heritage site.This universally accessible network, reinforced with secondary interconnections, will expand reaching out to still more sites, ultimately linking up the whole fabric of the city.

Not only will we have accessibility for all but also a strong message put out to the citizens to fight stratification at large. We recognize a change when the main access to the monument is universal, when the ramp is not in a lonely corner, but occupies the entrance to the shared heritage, when design accepts and respects our diversity. We recognize a change when we begin to reconsider our very principles of conservation of the built past! This is how architecture spearheads a reversal in our perception, a social change while exploiting the power of mass communication that architecture is capable of.

This proposal comes with the by-products of accessible tourism and revitalization of the built past, that add amongst other values, commercial appeal to social goals, proving that ‘out of adversity, comes opportunity.’

Architect Norman Foster acknowledges universal access as integral to design, a duty of architects- “Architecture is a social art - a necessity and not a luxury. It is generated by the needs of people, both spiritual and physical. It has much to do with optimism, joy and reassurance - of order in a disordered world, of privacy in the midst of many, of light on a dull day.’

Today there is a lot of buzz about upgrading Delhi to a ‘Smart City’, one with ‘world-class standards’ envisioned by Kamal Nath, Union Minister of Urban Development, and echoed in the masterplan2021. Prominent schools including ours are discussing, debating and developing this concept.

This ambition is meaningless and hollow if the most fundamental rights of its citizens are disregarded in the conception of the city. We conclude with an optimistic retelling of Meena and Sandeep’s games in a transformed Delhi. They still do enjoy a steeplechase, except with slightly different events. The race begins at the edge of the metro station square followed by running down the ramp onto the pavement, crouching sideways through the space between the lower bar (handrail for children) of the railing, followed by a quick one- legged run following the neatly laid out tiles on the pavement, all the way up to the sign board that indicates a pedestrian crossing ahead.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Working with People with Disabilities: An Indian Perspective, by Priya E. Pinto,and Nupur Sahur http://www.samarthyam.org Invisible Children,by Mithu Alur

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |