[ID:2319] “Architectural Response to Struggle and Transformation”India In front of the gate of the Union Carbide Factory, which lies abandoned for 32 years, there is a sculpture designed by Ruth Kupferschmidt. The sculpture depicts a woman holding an infant in her arms, covering her and her child’s face with her Saree, running, saving their life. Her other child, 3-4 years of age is running behind her. This piteous sculpture depicts of what could have had happened on the horrifying night of the 2nd Dec 1984, the night of Bhopal Gas Tragedy.

Bhopal Gas Tragedy is one of the largest chemical disaster in human history which caused death of more than 3,700 people, and near-fetal injuries to about 38,000 people due to the leakage of toxic MIC (Methyl Isocyanide) gas from Union Carbide India Limited factory (a pesticide factory in Bhopal, India). In this disaster many lost their eye sight, suffered from chronic diseases, disabilities or other health effects to respiratory tracts and neurological systems. Not only human but other forms of life such as dogs, cats, goats, buffaloes, cows, hens and other domestic animals and birds suffered by this incident, few of which were the part of lives and source of livelihood for many people at that time. Furthermore, soil and ground water were also contaminated which worsened the health of the people. The people living in slums around the area had to vacate their homes immediately which rendered them homeless and jobless.

The Situation emphasized for the work of rehabilitation. The government of Madhya Pradesh, where Bhopal is located, as well as the central government of India took various initiatives for the social, medical, economic and environmental rehabilitation for the people who directly or indirectly suffered from the tragedy. Family members of the deceased were given approximately 10,000 rupees (1000 USD) as compensation money at that time[*1]. Many free facilities were provided in the hospitals and some new hospitals were also opened dedicated to the gas victims.

Under the schemes of social rehabilitation, a total of 2486 housing units were constructed which were located in the vicinity of 3 km of the Union Carbide Factory in the outskirts of Bhopal city. These housing units were distributed in 1992 to the family members of the deceased or to people suffering from lifelong disabilities and those who lost their homes in the disaster. What started as rehabilitation program, in time with its unique demography and sentimental similarity today presents a 'housing' which possesses a strong notion of Communal Unity.

“When Qyamat (end of world) arrives, it does not see whether you are Muslim or Hindu. That day, nobody was Muslim, nobody was Hindu, nobody was man, nobody was animal, and everybody had the same fate! We could see rows of dead bodies on the streets.” These are the words of Md. Gulpham Khan who is living in this housing for 17 years. He lives with his wife, two children and mother-in-law. His father-in-law died in the tragedy and mother-in-law faced problem in the eyes. Talking about her, he joked, “Her husband died very early in life. Where would she have found a prince for her daughter? So, she married her off to me.” Mr. Khan is 47 years old and runs a general store in front part of his house. To have a talk with him, we went to his shop under pretense of buying chewing gums. After some time a girl also came to the shop. Mr Khan said, “Look! She is Preeti’s younger sister. She is from a Hindu family. I donated blood to Preeti when she was ill. You can ask her.” Preeti’s sister smiled slightly and then her expressions became serious. Mr Khan continued, “Since then, Preeti considered me as her brother and used to celebrate the festival of Raksha Bandhan (a Hindu festival girls celebrate with brothers) with me. Unfortunately her condition worsened after few years and she is no more now. Both our families still have good relations with each other. We often invite each other on any event or party”. “We don’t fight with each other, we live with love and peace”.

We talked to that gentleman for about an hour. Calmness on his face, his gentle nature and his talk about communal unity made us stick with him for that long. We wondered whether this story of communal harmony, was just a part between two family or the whole settlement represented it? And if the whole community really stands united, then does the suffering and struggle caused due to the disaster has any role to play in it? And how much does the design of the housing cluster contribute to this unity?

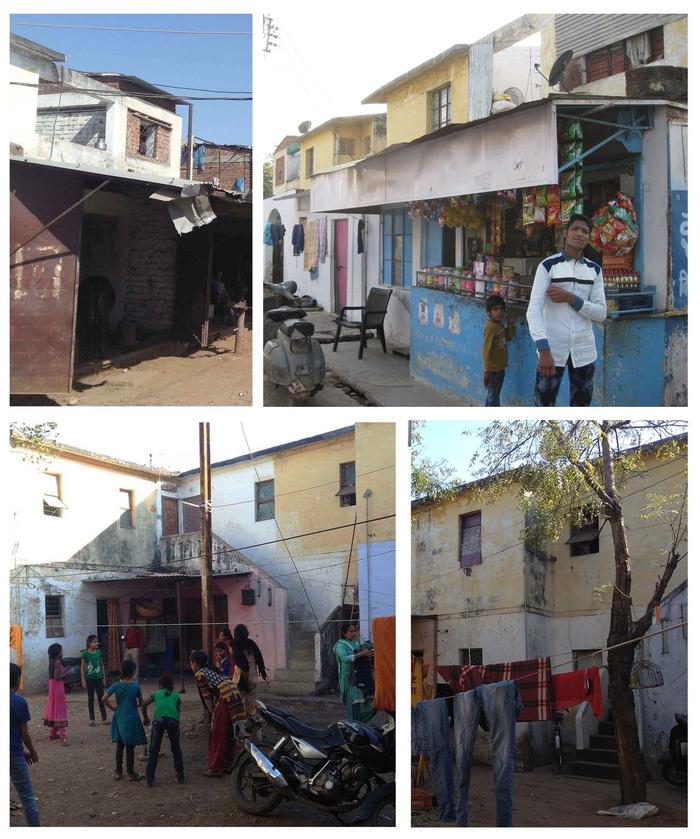

This rehabilitated housing is located in the outskirts of Bhopal and is named ‘Jeevan Jyoti’ (Light of life). People also call it as ‘Gas Rahat Colony’ (Gas Relief Colony) or ‘Vidhwa Colony’ (Widow’s Colony). All 2486 housing units are distributed around the site. Out of these, the units which are designed by Architect (Prof.) M.N. Joglekar are clusters of two storied buildings. Other units are designed as four storied buildings. The two storied clusters are arranged around big open grounds whose size varies from 25mX30m to 25mX60m. Each open ground surrounds eight to ten blocks. These blocks are arranged in such a way that there is a minimum difference of two meters between any two blocks. Each of these blocks has an arched entrance. As anybody enters to any of the blocks, he sees that there are four sub-groups each consisting of five housing units arranged around a central courtyard 10mx12m in size. In the sub-groups, the units are arranged such that there are three units on the ground floor and two units on the first floor. Thus there are 12 units on the ground floor and eight units on the first floor making a total of 20 units in each block. There are four staircases to access the units on first floor, each shared by the two units. Each housing unit has one kitchen, one bathroom and two rooms. One is complete and other is incomplete having neither roof nor walls, only post and beam. The purpose of this incomplete room is to provide scope of future expansion. People have used this opportunity according to their need and economic strength and converted the incomplete room into other rooms, or partially covered rooms, or ‘verandah’, or balcony, or shops etc. There is no architectural metaphor or symbolism for any intentional meaning. The facade of the buildings are plain. The walls were painted yellow which are now changed regularly according to the needs and inhabitant’s own choice of color.

Before the disaster these people lived in a very different fabric. There were boundaries between the housing clusters on basis of religious or economic grounds. Religious clashes often strengthen these divisions and made the heterogeneity evident. Cultural and social exchanges were limited to their community which most often was religion centeric, which in a way also gave them identity. But, the disaster very strongly affected their life, changing the identity they related to. They no longer were members of different community; they now were Victims or Survivors. Irrespective of their cast or religion, people came up, raised voice against the disaster, demonstrated their anger in thousands of rallies against the company’s negligence, and demanded for justice and rehabilitation. Architect Joglekar understood this shift and taking this community’s emerging unity and integrity in mind he comes up with a sensitive design which not only helps in their economical struggle but also satisfies their emotional needs and strengthens their sense of unity.

Design of cluster encourages community living by a compulsory interaction from individual household to neighborhood level. Common staircase for housing units of the first floor unites two houses and the common courtyard ties all the 20 units in a single thread. This courtyard gives an equal opportunity to use and take care of this open area to all the 20 units. As the floor area inside the house is nominal, many of the daily household functions are carried out in the courtyards. The courtyard, quite intuitively, creates a stage for recognition of recurring family events like birthdays, anniversaries and several other small social events. Children grow up with diversity, playing together in these spaces. A mutual respect automatically generates when visually interpreting, exchanging and retaining each others values, culture and tradition. Inhabitants have planted trees at the center of most of the courtyard thereby providing a shade for extending homes into the open, in summers, and share their emotions and presence amongst themselves.

The block where Mr. Gulpham Khan lives has eight Hindu families and 12 Muslim families. And Mr. Khan says that similar stories are there in every block with little differences. Although there is no perceivable demographical dominance in any of the blocks, one can visually trace incidents of religious symbolism, occurring in coherence. Hindus demonstrate their religious faith and practice by tiding red threads or cloths around the tree or deities made from small stones, at some corner inside some of the courtyards. Islamic faith and values are represented through overhung bands of small flags depicting the star and the crescent, running across the pathways. In this kind of demonstration, mutual understanding plays a role and people learn to accept individual sentiments and differences. We registered an example of communal love and respect at a small temple – some series of flags depicting the star and the crescent were hanging with ropes tied to the steel bars (used in construction) coming out of the temple. Asking around, we were informed that even Muslims in the cluster had contributed to the construction of the temple.

In search of some more evidence of communal unity and harmony we roamed around the open grounds around which the blocks are situated. Most of these grounds are plain and majorly used for outdoor sports. One such ground is named Ram-Raheem Maidan (‘Ram’ is a Hindu god while ‘Raheem’ is one the names of Allah in Islam, and ‘Maidan’ means ground), which is dedicated to religious practices, rituals, festivals and other big social events. This serves as the locus for the interpretation of both the communities. There is raised platform of size approximately 4mx6m. The platform is open from all side and shaded with galvanized iron sheets. People of both the religious groups use this platform to celebrate their festivals. At the time of festivals like Vijayadashmi and Ganesh Chaturhi (10 days long festivals) Hindus clean this platform, make a ‘Pandaal’(temporary house for God) with wood planks and colourful cloths, decorate it with colorful thermocol (Polyestene), put idols of various gods and goddesses inside, worship and celebrate. After celebration they dismantle it. Similarly Muslims during Muhrram (a month long festival in Islam) use the same ground to perform activities, celebrate and install ‘Tajiya’ on the same platform in a similar process. The dates of Muhrram and Vijayadashmi had clashed in the past two years. In such cases, Muslims willingly installed ‘Tajiya’ of Muhrram, without any dispute or estrangements, in the adjacent ground. In front of this platform there is an iron pole erected in the ground, where hangs the Indian National Flag, subduing the religious difference. Here Independence Day and Republic Day are celebrated in presence of everyone.

People also use this ground and platform for marriage ceremonies and relatable social, cultural or religious program and events. There is also an Aanganwadi (nursery) center where working women drop their babies for the day to go to work. The ground also has one hand pump for fresh drinking water of public use and dustbins for garbage collections

32 years have passed, the inhabitants still believe that they have not been given due justice. Warren Anderson (an American businessman) who was the CEO of the company at the time of disaster, died in Sept 2014, unpunished at the age of 93. People still hold him responsible for carelessness of the factory which led to the tragedy. In case of public demonstrations, marches, against the government or legal systems, or rallies for justice for the disaster, they gather in this ground where local leaders and social activists address them. Public demonstration of anger and emotions can be seen on the boundary walls of the abandoned factory or in adjacent newly constructed ‘Remembering Bhopal Museum’ (dedicated to the memory of the disaster).

There is a long going demand for justice and upliftment in the community. This holds true especially when one looks at the present condition of the buildings. The broken sewerage pipes, the leaking ceilings of some houses and structural decay in the houses show the poor economic situation of the people. Even the public and infrastructural needs are not up to the mark as it should be. The broken down roads, unmaintained grounds and the poor conditions of the public amenities reflect the failed attempt of government in fulfillment of their needs.

The scar of the tragedy is permanent, but it has fade away and is now on the transforming cartwheel for a new life and a beginning. The suffering of the past may not ever be healed but it had surely given birth to a new life form. Most of the family who first arrived at the community might not be living here anymore; new families would also in future come to live here who might not be having anything common to what the initial inhabitants shared with each other. And similarly the spaces will also transform its quality, but still it will be retaining the values, ambition and the zest which made the foundation of the community and created a culture in itself and this, thus, shall also be passed to the new inhabitants of the place.

There is an inherit desire among humans to create and propagate presence through cultural and social exhibition in society. What usually society used to create this belongingness is a shameful exhibition of social division based on race, religion and economy. But here in this small community, the connecting background, although the being unfortunate, is very profound. The need of a community is to support and give rise to each individual. The need of spaces is not just for shelter but to create a life, a life which is unique to its place and people. Here, each part of the system, right from people to houses to the daily drama of the place makes an attempt for this new start. And when we see the architecture simply allowing this growth to take place so beautifully, it makes us realize our responsibilities as architects and trust in social art of architecture to bring change into the world. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- References: 1."Madhya Pradesh Government: Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief and Rehabilitation Department, Bhopal". http://bgtrrdmp.mp.gov.in/relief.htm. Retrieved 28 Jan 2017.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |