Essay QuestionThe QuestionDESIGNING FOR THE PUBLIC GOODFIND A BUILDING IN YOUR COMMUNITY THAT SERVES THE PUBLIC - OR A SPECIAL POPULATION-- AND THAT YOU BELIEVE IS PARTICULARLY WELL-DESIGNED. WHO WAS THE ARCHITECT? WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE BUILDING? WHO DOES IT SERVE? WHY DO YOU THINK IT WORKS SO WELL? HOW HAVE ALL OF THESE FACTORS CONTRIBUTED TO ITS UNIQUE PUBLIC SIGNIFICANCE? 2012 Introductory EssayThis year's introductory essay is written by John Cary. John is editor of PublicInterestDesign.org and author of The Power of Pro Bono: 40 Stories about Design for the Public Good by Architects and Their Clients. A 2003 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley College of Environmental Design and its 2011 commencement speaker, John Cary has been a BERKELEY PRIZE committee member since 1999. REFLECTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE, COMMUNITY, & WRITING In the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, which devastated the U.S. Gulf Coast six years ago this fall, a woman named Martha Murphy managed to charge her cell phone in a car cigarette lighter and summon help. Her first call was to an unlikely destination: the New York firm of SHoP Architects. The town of Pass Christian, Mississippi, had been hit hard—effectively wiped off the map, with 100% of its business and 8 out of every 10 homes destroyed. “The first thing I realized after the storm,” Murphy explained, “is that a community is not its buildings; a community is something different and more.” But, she continued, “Our world was down, and it seemed incredibly important to see something go up. To be a community, we needed a structure; we needed a place to gather.”

Whether we’re talking about the extraordinary community center that SHoP ultimately designed in Mississippi, the celebrated “Birds Nest” designed by Herzog & de Meuron for the Beijing Olympics, or a humble thatch-roofed hut in a far more remote corner of the world, architecture is, at its core, a place to gather. This simple function is rarely without its challenges as fostering a sense of inclusion almost inevitably excludes some populations, whether intentionally or not. The challenge of this year’s Berkeley Prize essay competition is thus a matter of distinguishing architecture that excites alone, with architecture that inspires and serves. Architecture for the public good, after all, must do both. Architecture can be a beacon of hope and symbol of renewed prosperity in thriving and struggling communities alike. As author and philosopher Alain de Botton (Architecture of Happiness) has so eloquently explained, we are, “for better or worse, different people in different places. Architecture’s task is to render vivid to us who we might ideally be.” On a Rwandan hillside, overlooking a valley at once lush and bone dry, stands a building that in so many ways embodies architecture can and should be. A dignifying place to gather and to heal, the Butaro Hospital was designed by Harvard University students who graduated just months ago to focus fulltime on MASS, shorthand for a Model for Architecture Serving Society. The hospital they designed for the people of Rwanda, through the nonprofit Partners in Health, opened earlier this year, bringing state-of-the-art healthcare to a district of nearly 400,000 people where little care had been available previously. Beyond its beautifully crafted stone walls and spacious patient wards, the hospital is at its core a community space.

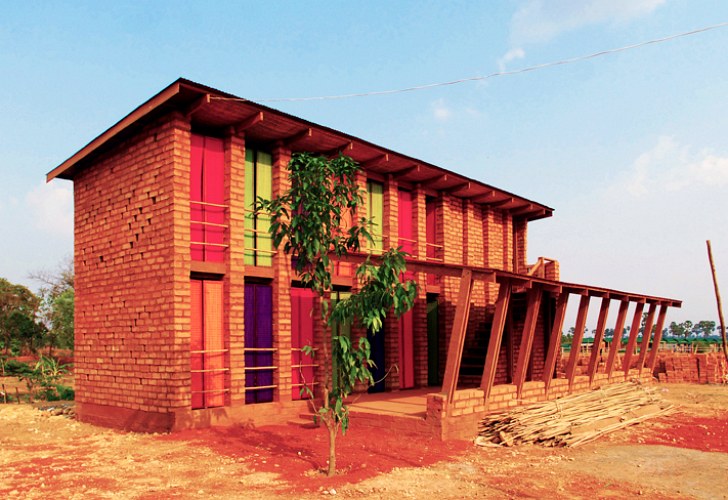

Elsewhere around the world, are equally inspiring spaces that serve. In Cambodia, the Sra Pou Vocational School by Finnish architects Rudanko + Kankkunen, is filled with children and bright accent colors between meticulously laid clay bricks. In South Africa, the Mapungubwe Interpretation Center, designed by architect Peter Rich and built by local craftspeople, while distinguished with extraordinary vaults designed by former BERKELEY PRIZE Juror, MIT Professor, and MacArthur Fellow John Ochsendorf, is nearly one with the landscape. It is easy fall in love with these unlikely examples architecture in even less likely places, while chastising high-budget buildings by the usual suspect stararchitects of our time. Yet each building deserves a more nuanced view. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Philip Jodidio’s book, Public Architecture Now!, showcasing projects by a who’s who of architects. Jodidio takes us first to France, where we see Jean Nouvel’s gleaming, snow white public pool complex, Les Bains des Docks, and then to Taiwan, to see Toyo Ito’s 2009 World Games Stadium, among dozens of other projects. Each exemplifies good design—even high design—aimed at serving the public, though never without challenges.

In his landmark book, called Better, author and doctor Atul Gawande offers some advice to those in his chosen field of medicine, but also to professionals of any kind, including architecture and design: “The published word is a declaration of membership in a community and also of a willingness to contribute something meaningful to it.” Whether your BERKELEY PRIZE essay proposal constitutes the first 500 words you’ve ever written or you are already a true believer in the power of the pen, it matters. It is a way of expressing yourself, your observations of your community, and your values—as architects and designers, as well as citizens of the world. While architecture education worldwide routinely honors students that keep their nose to the grindstone, working day and night in studio, this year’s BERKELEY PRIZE is an invitation to look up, walk outside your school, across campus, and deep into your community. It sounds like a simple challenge, but it can be equally exhilarating and terrifying. Like writing, truly taking part in the world around us is a sorely understated and even discouraged aspect of architectural education and practice. This competition call very well may be the first time you do so. It’s an opportunity to really see and listen to a place as well as the people occupying it. The more you look and listen, the more you will learn and understand about whatever space ultimately captures your interest. Nowhere in this essay or on this website will you receive marching orders for where to look or who to talk to; that’s for you to figure out and share.

We learned the harrowing details of Martha Murphy’s fateful call to SHoP Architects in those hours after the hurricane by asking her. We can not help but be captivated by the story of the Butaro Hospital as we listen the designers who lived and worked on the site for months on end recount their first impressions, how they were received, and who they met. Both are tales about the power of architecture and design. But they are tales comprised as much of words as of glass, steel, stone, and wood. And therein lies the power of writing and the beauty of the BERKELEY PRIZE essay competition. In that spirit, we invite you to contribute your voice and your observations of a space or place in your community that truly represents architecture for the public good—for you, and for others. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|