[ID:4598] COMMUNAL HARMONY IN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGNKenya Slum-dwellers in Kenya, especially in big towns and cities such as Nairobi, face multiple social issues, including lack of security of tenure. Apart from the universal problems in informal settlements, they face constant eviction threats from slum lords, the government, and private developers. Election periods are also extremely volatile and heighten their fears because their localities are usually some of the epicenters for post-election violence in case of political and tribal disputes. An example is the Kibera slum, which has remained resilient since pre-independence (1963- Kenya’s independence year) and has grown as a gateway to Nairobi for low-income earners moving from rural areas. There have been attempts at upgrading the slum with different levels of success. Still, some residents are willing to move from the city but stay within the metropolitan for easy commuter access to their jobs.

Numerous social organizations work within Kenya’s slum areas. The locals also group themselves into informal institutions to ensure communal progress with the hopes of making their homes more livable or to make it out of the slum. For example, the particular group discussed in this essay are part of Kaza Mwendo Housing Cooperative. The title of their organization translates from Kiswahili as “Pick up the pace.” Its members are traders in the informal Toi Market in Nairobi, with the older members being over forty years old while the younger ones are in their thirties. Their community encompasses single-parent and two-parent households with children of various ages ranging from 1-17 years old. In addition, these people have close ties with their relatives living in the countryside who sometimes move in with them as they transition from rural to urban life in search of better opportunities. Organizations such as their housing cooperative help ensure communal harmony such as cooperation in service installations, security for their children and homes in the slums, and collective saving schemes for personal and community projects.

These Kibera residents are aware of their contribution to the city. Even though each circumstance is unique, their situation is in many ways similar to other slum dwellers globally. For example, they service the wealthier parts of Nairobi such that for every affluent neighborhood, there is a slum that houses the workers (and their families) who provide domestic and industrial labor. This community has therefore been seeking help from governmental and nongovernmental organizations to relocate from the slum but retain access to the city. The people also took the initiative to set financial goals with equal targets for collective savings aiming to buy land in the counties neighboring Nairobi. Despite research fatigue due to the many studies done about their communities, their leaders willingly participated in case studies locally and abroad for them to diversify and weigh the options regarding housing. Their efforts date as far back as the early 2000s when they identified a piece of land they wanted and took out a loan to acquire it. Most of them have voiced their wishes for homes where they can raise their families, retire and pass down to their children thus attaining security of tenure is a crucial factor.

An appropriate project team to help the community would include construction industry professionals, local authorities, social organizations, and the clients - slum dwellers. So far, Kibera residents have shown great initiative, ability to organize and sense of community through the creation of collaborative saving schemes and social development groups. An appreciation for a working coordinated group with locally chosen leaders, and a common goal would be appropriate for their participation in the project team. A similar project targeting the same demographic can utilize organizations working in informal settlements to organize the community into such a coordinated group. Preliminary meetings would focus on getting the community on board, explaining what the project professionals and other team members offer and ensuring they feel empowered in providing their input about their future homes.

Meanwhile, the professional side of the team should also assemble with social workers who have been in contact with the community. At this stage, they should inform local authorities of their plans so that their inclusion will ease political issues that often set back disadvantaged groups especially considering that housing for low-income groups and slum dwellers has been a contentious topic in Kenya for decades. Additionally, governmental authority figures play a crucial role in terms of zoning regarding mass relocations or approvals of the construction processes to be undertaken. The overall team would then decide on meeting days and modes of communication. Online and physical spaces where the various stake holders can talk to each other and share ideas about the housing requirements while considering their daily activities or schedules would require effort and interest in showing up for the project to succeed.

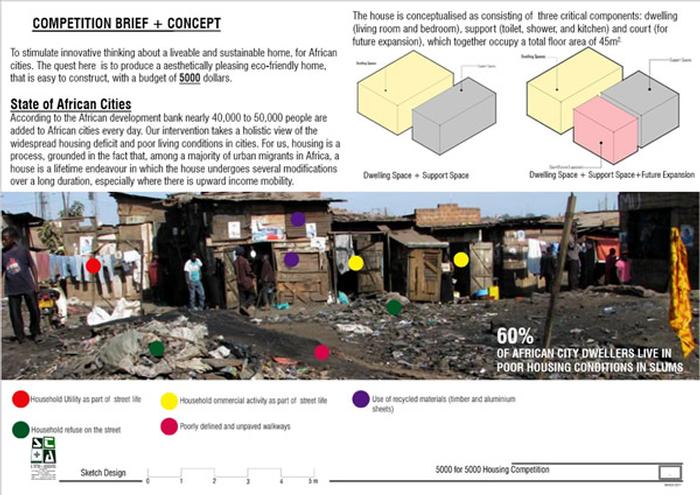

Questions for the users would cover social and spatial issues: What are the primary functions of your living spaces throughout the day? Families in the slums tend to make the most of the small area in their shanties, and figure out common spaces with neighbors. An understanding of their daily activities, the time, area and household members undertaking them would help in designing functional housing units. Notably, a home in the slums often takes up domestic and commercial functions especially when one or more family members work around the home. These activities include running small shops such as kiosks, milk bars, and providing hairdressing services at the front of the house. Therefore, it would be prudent to ask if the users would like to retain these uses in their future homes considering that they ensure convenience in the neighborhood. Their spatial requirements also differ from regular home functions and they present an issue in terms of a breach in privacy. One on one discussions would help users and designers identify and articulate solutions.

Who are the occupants of your homes, how many are they, and what are their ages? The people in a house and their relationships with each other would inform privacy, partitioning, room sizes and total unit areas. Do you temporarily share your spaces with other people, maybe relatives or neighbors, and how do you achieve that? Even though slums are an urban problem, the dwellers do not exist in a cultural vacuum. These places are a melting pot of numerous local tribes each with unique social practices. Designing for the users necessitates insight into their cultures especially for those with deep traditional tribal roots. Such ties often manifest when they take in relatives from their former rural homes or during events and visitations. In addition, their urban lifestyle presents a communal culture where the people around them are also space users of their home environment. Poverty also forces them to share certain services including toilets, bathrooms and kitchens. Generally, temporal or permanent shared spaces including circulation paint a picture that is fairly broader than one family unit, it shows the interaction that a housing scheme would enable.

What kind of homes do you envision; multi-storey apartments or single-family units? Part of the reason why some formal slum upgrading projects have failed is the lack of inclusion of the space users in deciding the type of homes that would suit them. For example, apartment buildings may make a community feel isolated especially when they are used to sharing facilities with neighbors. The same issue may arise when a household consists of numerous homes with related occupants in individual but interdependent families. Therefore, asking the specific users to choose what kind of building suits their lifestyle would be a possible better approach in meeting their needs. Some people would prefer single-family units but with a thriving neighboring environment while others may want multiple storeys with provision for social spaces, service placements and safe areas for their children. Other options are likely to arise during consultations.

How do your communities function in shared and open spaces? There is limited open space in slum areas but social halls and spaces in public schools during weekends and holidays usually serve the community. Available play grounds cater to children of school going age and young adults. Alleys, streets and roads sides also form part of the communal space. Creating homes away from the slum would thus require studies of their uses, hierarchies regarding sizes and importance, and optimum functionality. Exposing the future home users to industry and social experts would help them figure out arising issues such as the relationship between shared spaces and security. Better yet, the exposure should help them attain a housing project that mitigates their current problems such that they will not have to endure limited solutions that slum conditions present.

What are the approximate space sizes for each activity around the home? There is likely to be a notable difference between the available space in a shanty and in a housing unit at the proposed project. Activities that usually take space in crammed multipurpose areas may also be separated. A list of functions including storage and house-keeping such as laundry should match the users’ vision. Notably, in Kenya, many people hand wash their clothes and hang them out in the sun to dry. This activity also often provides an interaction space and time where a family or neighbors gather during the weekend to clean while they catch up with each other’s lives. Talks between the users and architects would help in allocation of these spaces such that they support their utilitarian and social aspects while maintaining the integrity and independence of each home. The approach applies for other uses such as outdoor kitchens since some of the cooking practices entail long processes or fuels that require open air in a semi-outdoor environment.

What amenities do you require in your immediate environment? Spaces that serve the community as a whole are a significant part of a collective housing project. No matter the type of buildings that the users prefer, the services that make their neighborhood more livable and family friendly have to be adequately catered for in the overall design. For example, garbage disposal methods and waste water treatment are crucial and differ depending on site conditions. In Kenya, areas around the Nairobi City Metropolitan with enough land to house a large number of people sometimes do not have direct connection to a sewer line or piped water. Such circumstances necessitate alternative solutions such as biodigesters or septic tanks. An introduction to companies that provide such products would help the users contemplate cost-effective options and learn their functions and maintenance. It could even present an opportunity to figure out extra income generating ideas such as animal rearing which could produce biogas through biodigesters that process animal waste. In some situations, there may be a main line some distance away from the site, thus the development will include costs to connect the project to that sewer.

Similarly, social amenities such as daycares, kindergartens, community halls, playgrounds and small medical facilities should be a discussion point. Their inclusion in the design or at least access to existing ones is crucial. A functional social housing project for low-income families with children should consider child safety through affordable means. For example, the solutions can provide child-care facilities and early education within walking distance from the homes in a walkable child-friendly neighborhood. Better yet, a deeper understanding of the community’s social dynamics can generate ideas on making child care a social function run by the users of that housing project; collective responsibility. In such discussions, construction industry experts should remember that these people have remained resilient in the slum through cohesion and have unique practices, expectations or goals for their children’s wellbeing and upkeep.

What construction materials do you prefer? The project team should make an analysis of local available materials and corresponding construction methods. Architects can also propose alternative technologies in conjunction with industry players to mitigate costs while working around other regular architectural considerations such as climate. The user’s input could inform the aesthetic and they could gain an education about all the available options. What is the approximate budget for an initial unit you would accommodate? The answer from the user would inform the architectural proposals and help the team decide on the level of initial construction, either for an incremental design or to build the entire project in one go. Comparisons with the average cost per square meter in the country would be a gauging point for the team in determining whether their ideas are efficient. The user’s willingness to provide informal labor during some parts of the building process would also increase their participation level and reduce costs. It would also give room for less technical designs.

Architects would then articulate the spatial needs and garnered information into construction drawings. Engineers could also optimize structural details; construction managers would recommend materials, and quantity surveyors would help determine the costs. These players would be in constant contact with the user through collaborative workshops, online and physically. This project team would work around the site forces in counties surrounding Nairobi, in small developing towns such as Mavoko and Juja. Mavoko is a semi-arid area in Machakos County, right next to Nairobi. It, however, has a high water table with aquifers and two rainy seasons. The site would be along tarmacked Kangundo Road, along which small urban centers are growing. Juja in Kiambu County is a bit more developed but still has large pockets of unused land. The area has wetlands and alternates between dry and wet seasons, but with constant water access from dams and boreholes. Residents in both areas commute to the city through public transport.

Social financing organizations would provide soft, zero, or low-interest loans for land acquisition and construction. Government parastatals would also chip in through funds for housing programs targeting this demographic, and the users could also contribute through a collective saving scheme. The users would actively participate in design and construction through regular consultations with them. For example, they could provide input about the allocation of functions on site when they visit it. Visual references such as images of buildings similar to what they want would inform materials and forms. Additionally, group activities such as creating life-size models of spaces using materials like cloth and sticks would give an impression of the space sizes they require. They could also learn to read plans and draw over prints of initial drafts to specify their wants.

This cooperative design would uphold the users’ dignity as part of society instead of the labels as needy forgotten people. The consultations would also ensure that the final design and built form last the community for the indefinite future through efficiency and adequate accommodation of their needs. All in all, collaboration and social inclusion in architecture is a proposal to develop a housing project suitable for communities living in Kenyan slums despite the issue being more nuanced than that. Creating a platform where users and architects interact while giving other stakeholders an advisory position would thus be a step in ensuring that housing schemes targeted to such clients are more practical, long-lasting and fitting.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |